Childhood Origins of Adult Resistance to Science

There has been considerable discussion about how to "frame" arguments about evolution, climate science, stem cells, etc. In the May 18th issue of Science, Paul Bloom and Skilnick Wisberg provide a cognitive scientists view of the problem. They attempt to explain the refusal of large numbers of citizens to acknowledge evolution while accepting the supernatural as everyday. This short review and the underlying cognitive research also has important implications for science education. Psychological studies have shown that from birth children form models of their physical environment that enable them to manipulate the world.

The problem with teaching science to children is, “not what the student lacks, but what the student has, namely alternative conceptual frameworks for understanding the phenomena covered by the theories we are trying to teach”[2].Surprising examples abound.For example, Bloom and Wisberg offer that a child soon learns that thing fall when dropped, but research has shown that this makes it hard for them to understand that the Earth is a sphere. After all, would not the people on the bottom of the sphere fall off the Earth? This is exacerbated by today’s ubiquity of digital media where things do not always function as limited by physical laws. A correct virtual simulation on a computer or video has no more validity than an incorrect one, and students are daily exposed to innumerable incorrect simulations in games and videos of all descriptions.

We have all seen cartoons where, as a joke, a character tunnels through the Earth, and comes out the other side, only to fall into space.This has an entirely different meaning to a young child than to an adult.

In a world filled with complex constructed visual images why should the image shown in a science class or an INTERNET applet be of more value than one in the video game the student plays after class (or sometimes during).

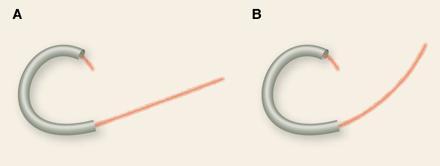

Bloom and Wesiberg offer an instructive example. In the figure at the left, students were asked whether a ball would follow the path shown in A or B after it leaves the curved tube. Although many chose incorrectly, it was found that actual observation could change minds and models. However, one must also realize that a simulation could show either A or B, and it is only the “real thing” that allows a proper differentiation. There is another barrier

Bloom and Wesiberg offer an instructive example. In the figure at the left, students were asked whether a ball would follow the path shown in A or B after it leaves the curved tube. Although many chose incorrectly, it was found that actual observation could change minds and models. However, one must also realize that a simulation could show either A or B, and it is only the “real thing” that allows a proper differentiation. There is another barrierThe examples so far concern people's common-sense understanding of the physical world, but their intuitive psychology also contributes to their resistance to science. One important bias is that children naturally see the world in terms of design and purpose. For instance, 4-year-olds insist that everything has a purpose, including lions ("to go in the zoo") and clouds ("for raining"), a propensity called "promiscuous teleology". Additionally, when asked about the origin of animals and people, children spontaneously tend to provide and prefer creationist explanations. Just as children's intuitions about the physical world make it difficult for them to accept that Earth is a sphere, their psychological intuitions about agency and design make it difficult for them to accept the processes of evolution.Often direct observation is not possible, or extremely time consuming. People learn to deal with these situations by evaluating the trustworthiness of the source that offers the information. This explains the central role of the teacher in learning and the difficulties associated with issues which have become entangled in faith and politics (evolution, climate change). It also explains why it is important to directly challenge those offering false information. The bottom line is

These developmental data suggest that resistance to science will arise in children when scientific claims clash with early emerging, intuitive expectations. This resistance will persist through adulthood if the scientific claims are contested within a society, and it will be especially strong if there is a nonscientific alternative that is rooted in common sense and championed by people who are thought of as reliable and trustworthy. This is the current situation in the United States, with regard to the central tenets of neuroscience and evolutionary biology. These concepts clash with intuitive beliefs about the immaterial nature of the soul and the purposeful design of humans and other animals, and (in the United States) these beliefs are particularly likely to be endorsed and transmitted by trusted religious and political authorities. Hence, these fields are among the domains where Americans' resistance to science is the strongest.These are truths that can cause one to despair, but they also offer insight into what must be done to educate people about science based issues and a more sophisticated analysis of the tactics that those who are spreading disinformation use.

26 comments:

How many of those questioning the extent of anthropogenic global warming are anti-science, in the sense that they are likely to be creationists or believers in astrology? Why aren't they simply hard-nosed empiricists?

"In the figure at the left, students were asked whether a ball would follow the path shown in A or B after it leaves the curved tube.'

I'd have to say "Bloom and Wesiberg offer an instructive example" of an exceedingly poor question.

Do these guys make questions for the GRE physics subject test, by any chance?

First, in the picture for A, the straight line path is not even parallel to a tangent to the tube at the point of exit! (it angles up a bit).

Second, if the tube is oriented vertically, the path of the ball after it exits will curve downward due to gravity

...unless the ball happens to be spinning when it emerges (in air, for example), in which case it might curve either up or down, depending on the detailed physical situation

(eg, how fast it was spinning when it entered and how much the movement through the tube (eg, rolling) affected the spin.)

--HA

Why aren't they simply hard-nosed empiricists?"

Some of them are. Freeman Dyson is one example, though he does not question that the CO2 buildup may cause a problem for humans, just the nature of the problem (h thinks the greatest threat is stratospheric cooling) and how best to deal with it (he believes we could solve it by growing more plants)

There is also another group who simply fancy themselves as "sceptics".

These are the "Einstein-wannabes" who equate (confuse) contrarianism with scientific skepticism.

"Einstein doubted -- and he was right and everyone else wrong. Therefore the simple act of doubting makes me another Einstein."

What these folks fail to realize, of course, is that Einstein's doubts were actually based on a very good understanding of physical reality (to say nothing of a brilliant mind) -- which seems to be seriously lacking among most of the "wannabe" crowd (especially the "brilliant mind" part)

Then, there is the third class who are simply dishonest. We all know who they are at this point. They are no longer fooling anyone -- except perhaps themselves.

--HA

I agree with you on the ambiguity of the question. I disagree with you on the characterizations of those who have questions about the extent of AGW. Have you read Aaron Wildavsky's But is it true? His is a position I find myself most in tune with.

The groups I mentioned above were not meant to be all-encompassing.

I don' disagree that some are simply "anti-science".

..and some (libertarian types) are just "anti-everything" that smacks of telling them how they can live their life.

--HA

The more I think about that example of the ball and the tube, the more apt it seems as an example of "Adult Origins of Childhood Resistance to Science".

It is the typical "true-false" (right-wrong) dichotomy that most adults are so enamored with and that our schooling system is based upon.

It is my guess that a lot of the misconceptions that children adopt at a fairly early age about science actually have their origin in the way that adults teach them about the world.

Anyone who has been around very young children knows that they are by nature very inquisitive and very "experimentally oriented" (hands-on).

Somewhere along the way, most of us lose that and I suspect that much of it has to do with being told the "right" answers by adults -- and being discouraged from actually discovering the answer.

Rather than encouraging kids to continue to observe their world and learn how it actually works, they simply tell them the "right" answer -- or what is worse, tell them that they are simply "wrong" when they are asking questions.

Of course, these "right" answers are colored by adults' own misconceptions and beliefs. And they are often not even right! (sometimes not even wrong).

'Just as children's intuitions about the physical world make it difficult for them to accept that Earth is a sphere, their psychological intuitions about agency and design make it difficult for them to accept the processes of evolution."

It couldn't be that the children were told by their parents somewhere along the way that God put us here, could it?

it really goes without saying that the things that one learns when one is very young (especially from one's parents) are often the hardest things to "unlearn" later on.

I think there are two separate audiences here: one is attitudes and predispositions of those with little formal knowledge of science, the second is attitudes and predispositions of those with significant backgrounds in science. There are strong similarities in the cognitive patterns of both: both are likely to confirm what they are predisposed to find. After all, most scientific methodologies have been developed to counter this strong tendency: it has not been surgically removed from the way we think.

The issue for the second group is ensuring the "quality" and "relevance" of the data upon which conclusions are based.

Bernie, Wildavsky was a political scientist and that book is fifteen years old. His views are relevant today because...?

OT, standards in Boulder seem to be slipping even further.

Steve,

At least RP is not trying to blame a significant fraction of global warming on dirty snow.

A while back, LM argued that positive feedback would have led to "exponentially increasing temperatures" in the case of the past CO2 increases shown by the ice cores. LM concluded that the fact that such exponential increase did not occur falsifies the positive feedback hypothesis.

Now, the dirty snow claim.

You really have to wonder what it takes to get a job at Haaavad these days.

It used to be pretty hard, I think.

Houston, we have a problem. Quoth the referenced article:

"The strong intuitive pull of dualism makes it difficult for people to accept what Francis Crick called "the astonishing hypothesis" (19): Dualism is mistaken—mental life emerges from physical processes. People resist the astonishing hypothesis in ways that can have considerable social implications."

In other words, Crick stated a controversial hypothesis and, um, it is true.

Typically there is a pretty dmaned compelling chain of argument from the hypothesis to blithe assertions of its truth in a prominent journal. Indeed, I would be hard pressed to come up with any logically parallel formulation in any formal publication. "Global warming is true"? Universal gravitiation is true"? Only in this application, where science is at its absolute weakest, is dogmatic assertion invoked. How peculiar. How damned peculiar.

Yet the monist proposition is fundamentally undecidable by any scientific methodology; experience has no objective measures and so no assertion about it, whether from AI people or eminent psychologists or anyone else, is scientific.

The bizarre way in which the truth of the very dubious proposition was asserted in the article is a pernicious feature of scientific culture. WHether or not it is true is undecidable in a scientific context, and it does not belong in the pages of a peer reviewed article.

This cavalier dismissal of the fundamentally mysterious nature of consciousness, a.k.a. the soul, alienates the general public. Meanwhile it is demonstrably not a valid statement in scientific discourse. Yet here it is again, marring what would otherwise have been a very valuable contribution.

Of course this is the issue about dualism to date, but the converse, to accept dualism is to accept that there is a metaphysics, call it God by any of his nine billion names and once you accept a metaphysics, physics completely loses its value, because you can always invoke metaphysics as a trump..

However, there are two technological outs. The first you can find by following the link. The second is modern neuroscience which is rapidly developing tools to probe the molecular origin of consciousness and of course the looming possibility of thought in silicon, which given the average value of thought in bioblobs, would be a good thing.

How do you scientifically approach the metaphysical consciousness?

How are you supposed to research the astral plane where the soul resides, if it by definition does not interact with the world except in the brain. Which part of the brain does it effect? The pineal gland? Etc.

These of course should be things to research, for dualism believing or dualism sceptic scientists. :)

-flavius collium

Wildavsky's relevance is fundamental to the scientific mind: The book originated in a request to his graduate students to find a proposition that predicted significant alarming outcomes in the future and then go out and get as many verifiable facts as possible and check to see whether the fact bases supported the propositions. Now in some instances the facts would be the results of scientific experiments, while in others it would simply be the clarifying of the meaning of numbers. For example, how much ice mass would be lost if the average precipitation in Antartica was reduced by 5% in one year - all other things being equal? (The vast majority of people do not have the foggiest idea of the size of Antarctica nor its precipitation, nor the thickness of the ice sheet, nor the average temperature, etc, etc. Many do not know the population of their own States, which makes assessment of their risks in response to a nasty event impossible.)

In the case of AGW the theory sounds plausible, the consequences are suitably alarming so what are the verifiable facts that support the contention? Each pronouncement as to imminent catastrophe motivates a new group of natural skeptics or students of Wildavsky to go out and check the fact base for themselves. If and when they find problems in the fact base they dig harder for more facts. In many instances they uncover gross misrepresentations of situations, in others the problem is appropriately "resized" and in others the danger proves to be as real as promised. Most skeptics are most definitely not beholden to oil companies or corporate polluters: they are, well, just skeptics.

The point here is that teaching science is about teaching people and kids to be both curious and skeptical. The same thought processes can be usefully applied to balls dropped from a tower in Pisa, the changing shape of a finch's beak and the existence of a Creator. Methinks the Apostle Thomas must be the patron saint of us skeptics and we are all from Missouri.

I don't believe consciousness can be related to physical science, like it or not.

There is no objective measure for subjectivity, and all else is handwaving and will always be,

It's dangerous handwaving at that. Suppose we replace ourselves with simulacra that pass the Turing test but don't actually have a subjective experience? How is that different from destroying the world?

That isn't my point here, though. My point is that this sort of question-begging isn't science and has no place in science. You don't prove controversial hypotheses by assertion, and in the present case there is no sensible test. Hence the whole question falls outside of science and shouldn't appear in Science.

As for framing science, an adamant materialist stance is not just naively sweeping the most important facts about reality under the rug. In practice it will not be popular with people who actually have an experience of the world, never mind an experience of the sacred.

Some experiences are not about facts but are about the nature of experience itself. These are facts of subjective evidence. That they are not amenable to objective methods doesn't make them less real as experiences.

People who lack experiences of the sacred should not presume to explain the nature of consciousness to people who have had them.

What anyone likes is irrelevant, nor is it written that there will never be an objective measure of subjectivity or that there will. Certainly the odds are better than finding a string.

OTOH, Michael your last statement is a mess. Should those who have had experiences of the sacred presume to explain the nature of conciousness to others. They as a class do not appear shy in doing so.

Should no one presume to try and understand the molecular basis of conciousness??

Finally, someone who has experienced the sacred, has to confront the base issue of dualism if he or she also wants to hold on to physics. Life is hard.

Yes, I'm a dualist. In fact I can't parse the logic behind the monist position. I don't argue against study of the chemistry of neural processes. I simply expect that any final connection between them and consciousness will always remain speculative, because consciousness is not measurable.

That's not the axe I am grinding here. My problem is that if what I am saying is off limits to science, the contrary position should be as well.

The fact that I am in a minority among scientists should not suffice for my point of view to be dismissed as "wrong" without argument or reference in an article in a peer reviewed journal.

The toxicity of religious dogma should not constitute an excuse for scientific dogma, which strikes me as equally dangerous.

I'd venture to say that consciousness is more like obscenity than it is like gravity.

We may not be able to measure the effects of consciousness the way we measure the effects of gravity, but, like obscenity, most of us nonetheless know it when we see it.

I suspect we will know it when we begin to see it in computers.

--HA

Eli, being a bunny, mostly does not care about soul insertion issues, but is more of the tooth and fang (and fast hopping and breeding) bunch. I am not sure that you are a minority among scientists, but there are consistency issues associated with dualism that reduce to don't know yet among monists. The dualist view is essentially a throw up the hands version, e.g. don't know, can never know, therefore.

We should study consciousness much like we study other phenomena, and it CAN yield useful results, for example in anesthesia. I've worked in the field myself in the past. If one can construct a machine that estimates the level of consciousness of a person, it's a useful device in minimizing drug overdosing.

The old school that talks about the chemistry of neural connections seems to miss the big picture - it's the configuration that's important, not the parts. I've heard a local old prominent neuroscientist fall to this kind of argumentation.

Complexity science and cybernetics which study steady states and feedbacks of systems are those that will probably make the most strides in the research of consciousness in the future.

I don't think we are yet at the point where one can say either materialism or dualism "is right", but we might some day be there, or then we might not. At the moment we just have hunches. I have a materialist hunch. I'd bet more money on that than in finding some spooky action receiving organ in the brain, or what ever the dualists propose as the mechanism of extramaterial consciousness interfacing with the material world.

But I'm not sure.

There are so many questions that Why shouldn't dualism be possibly scientifically evident?

What if we can build artificial conscious "brains"? Does dualism still hold? Or do dualists say those are not really conscious? It's tough to say of course, if one agrees that there are no real direct measurements for consciousness, at least not yet.

I'm sorry if this sounds aggressive, I'm honestly trying to probe your mind here.

-flavius collium

As an addendum, I am not sure that monism (which is IEHO a better description than materialism) is necessarily antithetical to religion.

Let me answer myself because this is about as subtle as the bunny gets and he has been called obscure by stoats.

The reason that I think dualism is not necessary to religion is the issue of an afterlife. If you believe in an afterlife (or a before life) you have to accept dualism. On the other hand if you don't you merely are accepting your own finite limit in time, which says nothing about God or religion as such (YMMV).

There are interesting and unending conversations about where the concept of an afterlife comes from BUT THIS IS NOT THE PLACE!!!!!

The problem we humans share is that our brains are a hodgepodge that evolution designed, not for rationaility, but to produce the next generation.

Scientists themselves struggle with the same cognitive problems that we all share, incuding the subconscious filtering and reality model defense that we engage in, which is one of the reasons for the old adage that science progresses, one death at a time.

"evolution designed"??

Isn't that oxymoronic?

anon - "evolution designed"??

Isn't that oxymoronic?

No.

Just adding a link to comment by a physics prof who's been encountering way too many confused-yet-confident undergraduates of the dextral persuasion.

(this is where the comment belongs)

Post a Comment